Shooting of Stephen Waldorf

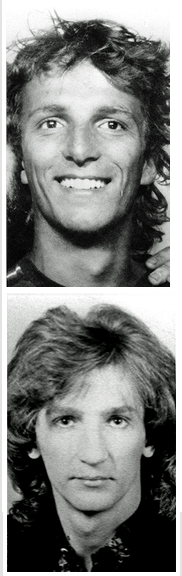

Stephen Waldorf was a 26-year-old man who was shot and seriously injured by police officers in London on 14 January 1983 after they mistook him for David Martin, an escaped criminal. The shooting caused a public outcry and led to a series of reforms to the training and authorisation of armed police officers in the United Kingdom. Martin was a cross-dressing thief and fraudster who was known to carry firearms and had previously shot a police officer. He escaped from custody in December 1982 and the police placed his girlfriend under surveillance. On the day of the shooting, they followed her as she travelled in a car whose front-seat passenger (Waldorf) resembled Martin. When the car stopped in traffic, Detective Constable Finch—the only officer present who had met Martin—was sent forward on foot to confirm the passenger's identity.

Finch, an armed officer, incorrectly believed that Waldorf was Martin and that he had been recognised. He fired all six rounds from his revolver, first at the vehicle's tyres and then at the passenger. Another officer, believing that Finch was being shot at, fired through the rear windscreen. As the passenger slumped across the seats and out of the driver's door, a third officer, Detective Constable Jardine, opened fire. Finch, having run out of ammunition, began pistol-whipping the man. Only after he lost consciousness did the officers realise that the man was not Martin. Waldorf suffered five bullet wounds (from fourteen shots fired) and a fractured skull. Finch and Jardine were charged with attempted murder and causing grievous bodily harm. They were acquitted in October 1983 and later reinstated, though their firearms authorisations were revoked. Waldorf recovered and received compensation from the Metropolitan Police. Martin was captured two weeks after the shooting following a chase which ended in a London Underground tunnel. The incident became the subject of several documentaries and was dramatised for a television film, Open Fire, in 1994.

Two months after the shooting, new guidelines on the use of firearms were issued for all British police forces; these significantly increased the rank of an officer who could authorise the issuing of weapons. The Dear Report, published in November 1983, recommended psychological assessment and increased training of armed officers. Several academics and commentators believed these reforms exemplified an event-driven approach to policymaking and that the British police lacked a coherent strategy for developing firearms policy. Several other mistaken police shootings in the 1980s led to further reforms, which standardised procedures across forces and placed greater emphasis on firearms operations being conducted by a smaller number of better-trained officers, to be known as authorised firearms officers, and in particular by dedicated teams within police forces.

Background[edit]

In the Metropolitan Police (the Met) in 1983, selected officers, including some detectives working in plain clothes, were trained to use pistols (the vast majority of British police officers do not carry firearms). The weapons were kept at certain police stations and could be withdrawn by authorised officers with the permission of an officer of inspector rank or higher. The Met also had a dedicated Firearms Unit (known by the designation D11)—officers who specialised in armed operations and had access to heavier weapons—which could be called upon for complex or protracted incidents.[1][2]

The police officers who shot Waldorf were hunting David Martin, an escaped cross-dressing criminal who was considered to be extremely dangerous. Martin had repeatedly used violence to resist arrest and had previously escaped custody, or attempted to escape, on multiple occasions. He had served a nine-year prison sentence, starting in 1973, for a series of frauds and burglaries. His sentence was originally eight years but he received an extra year for his role in a breakout. He was released in 1981 and resumed his criminal career.[3] He committed a series of burglaries, including one in July 1982 in which he stole 24 revolvers and almost 1,000 rounds of ammunition from a gunsmith's shop. From then on, Martin carried two guns wherever he went. He committed several armed robberies with the stolen guns, including one in which a security guard was shot. In August 1982, police officers caught Martin in the act of burgling a recording studio but he shot his way out, seriously injuring one of the officers.[4][5]

Police put Martin's girlfriend under surveillance and Martin eventually turned up at her flat dressed as a woman. When confronted by a police officer (who initially thought he was talking to a woman), a struggle ensued and Martin produced a gun. Another officer shot Martin who, although hit in the neck, continued to resist and produced a second gun. Martin was overpowered and taken to hospital, where it was discovered that the police bullet had broken his collarbone. He was discharged from hospital into police custody in September 1982.[6][7] Over the following three months, Martin made multiple appearances at Marlborough Street Magistrates Court, charged with attempted murder and other offences. He was kept on remand at Brixton Prison and escorted to and from court under heavy guard. On 24 December, while waiting for his hearing, Martin escaped his cell and fled across the roof of the court building, prompting a large manhunt which was run by a dedicated task force.[5][8][9]

Shooting[edit]

The task force again followed Martin's girlfriend, with the help of C11 (a unit of specialist surveillance officers), hoping she would lead them to him. If they encountered Martin, the plan was to follow him to a premises and await the arrival of D11, though several detectives and surveillance officers were armed in case of a confrontation in the open.[10] On the evening of 14 January 1983, police observed Martin's girlfriend get into a friend's car, which they covertly followed through West London. After about an hour, she left the vehicle and was picked up by a yellow Mini. The police tailed the Mini, in which she was a back-seat passenger, along Pembroke Road in the Earl's Court district. In the front passenger seat was an unidentified man whom the officers believed resembled Martin.[11][12]

When the Mini came to a halt in traffic, Detective Constable Finch was sent forward to confirm the front-seat passenger's identity. Finch had been present at Martin's previous arrest and was the only officer in the convoy who had met Martin; the other officers could only identify him from photographs.[8][13] Finch, who had been in a vehicle two cars behind the Mini, drew his revolver as he approached the suspect vehicle. Finch incorrectly identified the passenger as Martin and believed that Martin had recognised him. The passenger reached onto the back seat, which Finch misinterpreted as Martin reaching for a gun. Without warning, Finch fired all six rounds in his weapon, first at the vehicle's rear passenger-side tyre and then at the passenger. The driver of the Mini jumped out of the car and fled on foot. While Finch was firing, a second officer, Detective Constable Deane, began shooting at the passenger through the rear window. Deane later stated that he opened fire because he believed he was witnessing an exchange of fire between Finch and the passenger. A third Detective Constable, Jardine, arrived to see the passenger slumped across the driver's seat and hanging out of the car door. Jardine believed the passenger was reaching for a weapon and fired three times.[14][15] The subsequent investigation found that the officers had fired a total of 14 shots.[8][16][17]

The passenger was hit several times and seriously injured. After running out of ammunition, Finch verbally abused him and pistol whipped him until he lost consciousness.[8][16][17] He was then handcuffed and dragged to the side of the road. At this point, it was discovered that the passenger was not Martin but Stephen Waldorf, a 26-year-old film editor. Waldorf suffered five bullet wounds—which damaged his abdomen and liver—as well as a fractured skull and injuries to one hand caused by the pistol whipping.[16][18] Martin's girlfriend was grazed by a bullet. Both were taken to St Stephen's Hospital. Within an hour, a senior officer at Scotland Yard issued a public apology and promised an immediate investigation by the Metropolitan Police's Complaints Investigation Bureau (CIB).[16][19] He described the incident as "a tragic case of mistaken identity".[16] Waldorf was in hospital for six weeks. When he regained consciousness, a senior Met officer visited him to apologise.[16][20]

Aftermath[edit]

The CIB investigation began almost immediately, led by Detective Chief Superintendent Neil Dickens. Dickens and his team conducted initial interviews with all the officers involved in the shooting within hours and then again the following day.[21] The incident attracted considerable scrutiny from journalists and the public, who expressed concern at the lack of restraint shown by the officers, the danger their actions posed to the public, and the potential breach of police policies on the use of firearms. The matter was raised in parliament. The Home Secretary, William Whitelaw, promised that the CIB report would be reviewed by the independent Police Complaints Board (PCB) and passed to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) to consider whether criminal charges should be brought against the officers. Whitelaw further promised that he would take steps to ensure that no such incident could happen again.[16][22]

The three officers who fired their weapons were suspended from duty during the investigation.[16] Finch was a local detective; Deane and Jardine both worked for C11. Deane was later reinstated when the DPP declined to bring charges against him. Five days after the shooting, on 19 January, Jardine and Finch were charged with attempted murder and inflicting grievous bodily harm with intent; Finch was charged with a second count of grievous bodily harm in relation to the pistol whipping. They went on trial at the Old Bailey in October 1983. Their defence teams argued that they had a genuine, albeit mistaken, fear for their lives. They were acquitted of all charges.[5][23][24]

In protest at the decision to prosecute Finch and Jardine, multiple armed officers relinquished their firearms authorisation. The Police Federation, which represents rank-and-file officers, suggested that armed police officers should be given a degree of legal immunity for actions taken in the course of their duties.[25] Following the trial, the CIB report was considered by the PCB and the Met's deputy commissioner (who oversees disciplinary issues), who concluded that the officers would not face disciplinary proceedings. They were returned to duty, though their firearms authorisations were withdrawn and Finch was returned to front-line policing duties.[26][27]

Waldorf eventually made a full recovery. He sued the police, who did not contest the case, and was awarded compensation (variously reported as £120,000 and £150,000) in an out-of-court settlement early in 1984.[17][28][29] Martin's girlfriend also sued the Met and was awarded £10,000.[29]

Later events[edit]

As a result of the Waldorf shooting, the manhunt for David Martin was taken away from local detectives and assigned to the Flying Squad.[30] Martin's girlfriend was charged with handling his stolen property and released on bail. In exchange for leniency, she agreed to help the police recapture Martin and set up a date with him at a restaurant in Hampstead on 28 January 1983. Over 40 officers, many armed, lay in wait for him. Martin spotted the officers and a foot chase ensued, which entered Hampstead tube station. Martin jumped onto the tracks and ran into the tunnel towards Belsize Park. He was arrested by armed officers after hiding in a recess in the tunnel.[31] Martin was charged with 14 offences, including the attempted murder of a police officer and multiple counts of robbery and burglary. He stood trial at the Old Bailey in September 1983, was found guilty, and was sentenced to 25 years' imprisonment. Martin took his own life in prison in March 1984.[23][32]

Several documentaries have been made about the incident. The first was an episode of TV Eye, broadcast on ITV on 14 December 1983, which included a reconstruction of the events. Waldorf contributed to the programme and described it as a fair representation of events. The Police Federation called it "trial by television" and felt that it would prejudice potential disciplinary proceedings against the officers.[33] In 1994, the same channel broadcast Open Fire, a made-for-television film by Paul Greengrass. The film, starring Rupert Graves as David Martin, dramatised the manhunt for Martin and Waldorf's shooting, including the subsequent investigation. An episode of the BBC's flagship current affairs programme Panorama, titled "Lethal Force" and featuring an interview with Waldorf, was broadcast in December 2001.[34]

Effects on policing[edit]

The shooting caused significant public concern and was discussed extensively in the media. According to Dick Kirby, a retired police officer and police historian, "there was such a public outcry following Waldorf's shooting that the government knew something had to be done with regards to police firearms training".[35] The Metropolitan Police commissioner's annual report for 1983 acknowledged that "professionalism, declared policy, and training failed" to prevent the incident.[36] In March, two months after the shooting, Whitelaw issued a circular to all police forces in England and Wales, titled "Guidelines on the Issue and Use of Firearms by Police". Individual forces previously set their own policies but were effectively compelled to implement the new national guidelines. The guidelines raised the minimum rank of an officer who could authorise the issuing of firearms from inspector to a much more senior officer (commander in London; assistant chief constable in all other forces). A superintendent could grant authorisation in an emergency, when lives were at risk, but a sufficiently senior officer was required to be notified as soon as possible and the more senior officer had the option to rescind the authority.[17][37][38] With regards to training, the guidelines stated:

Every officer to whom a weapon is issued must be strictly warned that it is to be used only as a last resort where conventional methods have been tried and failed, or must [...] be unlikely to succeed if tried. They may be used, for example, when it is apparent that a police officer cannot achieve the lawful purpose of preventing loss, or further loss, of life by any other means.[39]

Whitelaw also convened a working group with a brief to "examine and recommend means of improving the selection and training of police officers as authorised firearms officers, with particular reference to temperament and stress".[38] The party was chaired by Geoffrey Dear, a Metropolitan Police assistant commissioner. It published its conclusions, which became known as the Dear Report, in November 1983. Among the recommendations were that all potential firearms officers should undergo psychological testing before selection, that initial firearms training should be more extensive, and that refresher courses should be more frequent.[38][39][40]

The Metropolitan Police implemented the first two recommendations but the third was indefinitely postponed because of budgetary concerns, partly because the Met was in the middle of a major restructuring.[39][41] The increased training focused in particular on Section 3 of the Criminal Law Act 1967, which codified the use of reasonable force in self-defence or to prevent the commission of a crime.[17] The working group standardised practices across police force. Among those, the term "authorised firearms officer" (AFO) became the standard national designation for a police officer trained in the use of firearms.[38] The group's work resulted in the publication of the first Manual of Guidance on Police Use of Firearms, under the auspices of the Association of Chief Police Officers.[22][42][43]

An article in The Independent ten years after the incident described the incident as "the error to force change".[16] The criminologists Peter Squires and Peter Kennison, in a study on police use of firearms, compared Waldorf's shooting to several other mistaken police shootings.[44] They believed that the shooting, particularly the way that other officers opened fire after hearing the initial shots, suggested "a 'gung-ho' attitude to firearms discharge falling well short of professionalism",[45] a view shared by Maurice Punch, another academic specialising in policing. Punch concluded that the "unprofessional, almost chaotic" nature of the incident raised "critical questions" about the command and control of the operation.[40] Timothy Brain, a former chief constable and author of a history of British policing, described the incident as "a disaster for the Met". He went on to say that "the episode seemed to confirm what critics [...] were asserting more generally, that the police were out of control and oppressive".[46] Squires and Kennison's thesis was that there is no coordinated approach to the development of police firearms policy in Britain, and that the response Waldorf's shooting was an example of the British police's event-driven policy making. They noted that the reforms emanating from the Dear Report did not prevent similar incidents, and believed that "each incident exposed failings at several levels of police critical incident management and execution".[47]

The use of firearms by police had long been the subject of debate in Britain. Although officers carried weapons for certain duties, many politicians and senior officers were keen to preserve the image of an unarmed police force. The debate was particularly intense throughout the 1980s, fuelled by a series of policy developments and several questionable shootings, including Waldorf's.[48] In 1986, the Home Office established another working group to build on the Dear Report, following two more mistaken police shootings—those of Cherry Groce, which sparked the 1985 Brixton riot, and John Shorthouse, a five-year-old boy accidentally shot dead in Birmingham.[22][49][50] Peter Waddington, a sociologist specialising in police policy on the use of force, suggested that these incidents, taken together with Waldorf's shooting, caused a permanent shift in the public's perception of armed policing and that police shootings—even of armed criminals and where police procedure had been followed correctly—became much more controversial from then on.[51] The report endorsed Dear's recommendations on training and selection of AFOs. Its main recommendation was that police forces place greater emphasis on specialist teams of armed officers, such as the Met's D11, and concentrate the use of firearms on a smaller, but better-trained, group of officers.[52] It also suggested research into roving armed patrols, which in the 1990s became armed response vehicles,[49] and recommended that local detectives (as Finch was) should no longer be AFOs; members of central squads (such as C11 or the Flying Squad) would be the only plainclothes officers to hold AFO status. As a result of these reforms, the number of AFOs in the Met reduced by about almost half over the following decade. Many of the report's other findings were overtaken by the 1987 Hungerford massacre, which prompted further reforms to armed policing.[52][53][54] In a 2023 book chapter, Squires argued that the effects of Waldorf's shooting continued to be felt and that the lessons from it and other incidents remained relevant.[55]

See also[edit]

- Police use of firearms in the United Kingdom

- Shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes (2005), another mistaken-identity police shooting incident in London

References[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Benn, Melissa; Worpole, Ken (1986). Death in the City. London: Canary Press. ISBN 9780950996745.

- Brain, Timothy (2010). A History of Policing in England and Wales from 1974: A Turbulent Journey. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199218660.

- Gould, Robert; Waldren, Michael (1986). London's Armed Police. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 9780853688808.

- Ingleton, Roy (1996). Arming the British Police: The Great Debate. London: Frank Cass & Co. ISBN 9780714642994.

- Kirby, Dick (2016). The Wrong Man: The Shooting of Steven Waldorf and the Hunt for David Martin. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 9780750964135.

- McKenzie, Ian K.; Gallagher, Patrick (1989). Behind the Uniform: Policing in Britain and America. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf. ISBN 9780745006307.

- Punch, Maurice (2011). Shoot to Kill: Police Accountability, Firearms, and Fatal Force. Bristol: The Policy Press. ISBN 9781847423160.

- Rogers, Michael David (September 2003). "Police Force! An Examination of the Use of Force, Firearms and Less-Lethal Weapons by British Police". The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles. 76 (3): 189–203. doi:10.1350/pojo.76.3.189.19443. S2CID 110817892.

- Smith, Stephen (2013). Stop! Armed Police! Inside the Met's Firearms Unit. Ramsbury: The Crowood Press. ISBN 9780719808265.

- Squires, Peter (2023). "Armed Responses and Critical Shots: Learning Lessons from Police-Involved Shootings in England and Wales". In Clare Farmer; Richard Evans (eds.). Policing & Firearms: New Perspectives and Insights. London: Springer. pp. 81–102. ISBN 9783031130137.

- Squires, Peter; Kennison, Peter (2010). Shooting to Kill?: Police Firearms and Armed Response. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470779279.

- Waddington, P. A. J. (1991). The Strong Arm of the Law: Armed and Public Order Policing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198273592.

- Waddington, P. A. J.; Hamilton, Malcolm (February 1997). "The Impotence of the Powerful: Recent British Police Weapons Policy". Sociology. 31 (1): 91–109. doi:10.1177/0038038597031001007. ISSN 0038-0385. JSTOR 42855771. S2CID 146122497.

- Waldren, Michael (2007). Armed Police: The Police Use of Firearms Since 1945. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 9780750946377.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Punch, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Waldren, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 42–53.

- ^ Kirby, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Smith, p. 57.

- ^ Kirby, p. 76.

- ^ Waddington, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d Squires & Kennison, p. 72.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Kirby, p. 92.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Ingleton, p. 86.

- ^ Kirby, p. 102.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Ingleton, pp. 84–86.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The error to force change". The Independent. 10 January 1993. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, p. 58.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Kirby, p. 117.

- ^ Benn & Worpole, p. 57.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 129–140.

- ^ a b c Squires & Kennison, p. 75.

- ^ a b "Man shot by police hunting David Martin". BBC News. 14 January 1983. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Benn & Worpole, p. 61.

- ^ Kirby, p. 218.

- ^ Gould & Waldren, p. 188.

- ^ Benn & Worpole, p. 58.

- ^ a b Kirby, p. 228.

- ^ Kirby, p. 147.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 165–172.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 195, 206, 226.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Kirby, p. 229.

- ^ McKenzie & Gallagher, p. 145.

- ^ Kirby, pp. 229–230.

- ^ a b c d Waldren, p. 94.

- ^ a b c Kirby, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b Punch, p. 108.

- ^ Waldren, p. 96.

- ^ Waldren, p. 95.

- ^ Summers, Chris (24 July 2005). "The police marksman's dilemma". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 September 2005. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Squires & Kennison, p. 148.

- ^ Squires & Kennison, p. 195.

- ^ Brain, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Squires & Kennison, p. 195.

- ^ Waddington & Hamilton, p. 102.

- ^ a b Waldren, p. 127.

- ^ McKenzie & Gallagher, p. 144.

- ^ Waddington, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Rogers, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Squires & Kennison, p. 76.

- ^ Punch, p. 50.

- ^ Squires, p. 84.